Copyright © 2010 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc.

Volume 56, No.3 - Fall 2010

Editor of this issue: M. G. Slavėnas

LITHUANIAN

QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES

|

ISSN

0024-5089

Copyright © 2010 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc. |

|

Volume 56, No.3 - Fall 2010 Editor of this issue: M. G. Slavėnas |

Stained Glass Artist Albinas Elskus and his “Forbidden Fruits”

STASYS GOŠTAUTAS

Abstract

Albinas Elskus (1926-2007), whose name in Lithuanian was Bielskus,

was not the ordinary stained glass maker. He belongs to the generation

of Lithuanian artists who in the 1960’s rediscovered Gothic

Cathedrals

and Tiffany glass and re-invented stained glass influenced by

Art Nouveau and Art Deco. Albinas Elskus, the

“Master,” as he was

called by his piers and contemporaries, was probably the best of them.

He worked steadfastly for five decades. More than a hundred churches

possess his stained glass decorations. Elskus used stained glass not

just for liturgical purposes but as a pure art form and left an amazing

legacy. Two years after his death, Beatričė Kleizaitė-Vasaris published

a bilingual monograph in Lithuania: Albinas Elskus, Artist of Beauty

and

Vision, (Vilnius: M.K. Čiurlionis National Museum of Art,

2009).

|

| Albinas Elskus, ca. 1950 |

The Lithuanian postwar generation of artists who immigrated to the USA became known as the glassmaker generation: V.K. Jonynas, A. Valeška and his brilliant student B. Jameikienė, V. Vizgirda and V. Ignas. For many years they made a good living working on stained glass for churches. The building and rebuilding of many churches demanded new artists and new techniques. The Lithuanian artists came just in time and left an amazing legacy. Albinas Elskus, “the master,” as his peers and contemporaries called him, was probably the best of them all. Not one of this generation is still alive today, and no new generation has emerged to replace them.

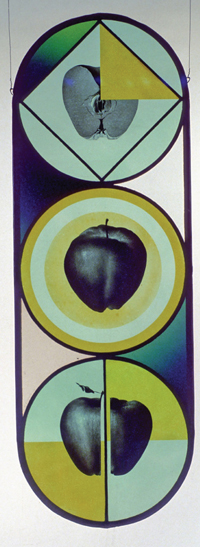

Albinas Elskus (1926 – 2007), whose name in Lithuanian was Bielskus, was not an ordinary artist in stained glass. He belongs to the generation of the 1960s that rediscovered Gothic Cathedrals and Tiffany glass and reinvented stained glass influenced by Art Nouveau and Art Deco. Stained glass makers were fascinated with the fresh possibilities of painted glass. In an age that pursued originality at all cost, Elskus achieved it with a medium rooted in tradition. He used stained glass not just for liturgical purposes, but also as a pure art form. Like some painters of the late Renaissance and a few in the neoclassical period, he was fascinated with still lifes, which he called “forbidden fruits”: apples, roses, and strawberries, all exquisitely painted on stained glass. His “Three Apples,” a masterpiece, is Albinas Elskus, ca. 1950 now part of the permanent collection of the Corning Museum. He had a passion for apples, which he liked to paint on glass, each time with a fresh, new approach. Called “Metamorphosis,” or “Spring,” or “Eclipse of the Sun,” his apples appeared in the semiabstract environment of stained glass artistry.

Elskus was neither a pure realist nor a pure abstract painter. He combined styles as partners rather than opponents. He never repeated himself; each work was newly designed and executed, probably because he loved to draw and did so with ease. He was also an exceptional watercolorist. But painting on glass and the art of glassmaking, which he did not consider to be a craft, was his passion. Painting on glass gave him more freedom than regular painting because it could be done on both sides. Elskus tells an interesting anecdote about the versatility of working with glass. He composed his “Female Nude” (1976) after having dropped and broken it by accident and then reconstructing this amazing work from the broken pieces.

Of course, he created many traditional liturgical windows. More than a hundred churches possess his stained glass decorations. Elskus’s deep faith and belief in the goodness of God, the ultimate Artist, make his church decorations convincing. They were His shadow on earth.

He enjoyed being a Lithuanian, but in his art he was a cosmopolitan with no national ties, viewing art as universal. His main contribution to Lithuanian art was the subtle ceiling mosaics he produced in 1966 for the Our Lady of Šiluva chapel at the National Shrine of the Immaculate Conception, in Washington, D.C.

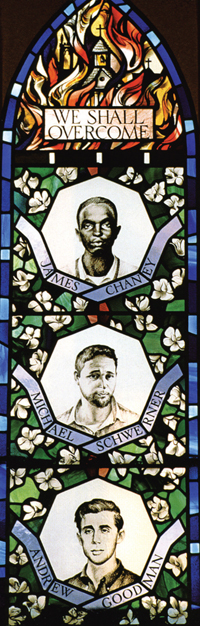

Elskus worked steadfastly for five

decades. Among his

best-known works is the Civil Rights Memorial Window (1991)

for Cornell University’s Sage Chapel to commemorate the three

civil rights activists murdered in 1964. He made a window for

the Playboy Club in Cincinnati in 1975 and another for the

Children’s

Pavilion at Mt. Sinai Medical Center, New York, in 1990.

|

|

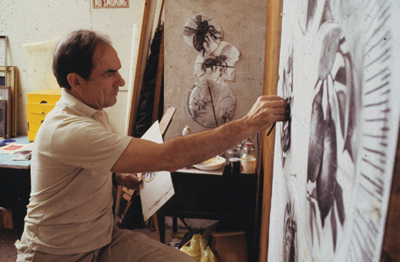

| Working on the berry for "Nature’s Citric", 1978. |

Working on cartoon for "Nature’s Citric", 1978. |

Elskus was an inspiring teacher who loved to share his knowledge and technique with his students. He taught at the Parson School of Design at Fordham University and was particularly famous for his demo lectures. Some twenty-five years ago he made an 8mm silent film, now a DVD, as a visual supplement to his book The Art of Painting on Glass [NY: Scribner’s, 1980]. His book, written at the request of his students, became a classic and is still sought after. “Here we can see for ourselves how one of the great and amazing artists of the world works on glass,” say Rona Moody and Tony Bankfield in Stained Glass Quarterly. He always criticized his own work and was a good art critic.

I met Albinas many times in New York and Boston and admired his workmanship, his knowledge, and his gentle, nonpretentious personality. Like other émigré artists of his generation, he began his studies in Kaunas, Lithuania, and continued after the war at the École des Arts et Métiers in Freiburg, established by V.K. Jonynas. He came to the United States in 1949, and started as an apprentice at the Karl Hachert Studio in Chicago. He had been fascinated with stained glass windows since art school and had traveled to Italy and France to study the famous cathedrals there. He established himself in New York in 1953, designing and painting for George Durham & Son; in 1964 he became a partner. At the end of his life, Elskus found full freedom and worked as a freelance artist. In the last eight years of his life, 1991-1997, he was commissioned to decorate the Gate of Heaven Chapel-Mausoleum in the Gates of Heaven Cemetery in East Hanover, N.J. Midway he suffered a stroke, yet was able to finish it. He created one of the most beautiful mausoleums in the United States, a monument for the cemetery and to himself.

Two years after his death, his lifelong friend Beatričė Kleizaitė-Vasaris published a bilingual monograph in Lithuania: Albinas Elskus, Artist of Beauty and Vision [Vilnius: M.K. Čiurlionis National Museum of Art, 2009]. It is an excellent biography, profusely illustrated and modestly documented. Some years ago, Kleizaitė-Vasaris included some seventy pages on Elskus in a previous book, Lithuanian Artists’ Works in the Sanctuaries of North America [Vilnius, 2004].

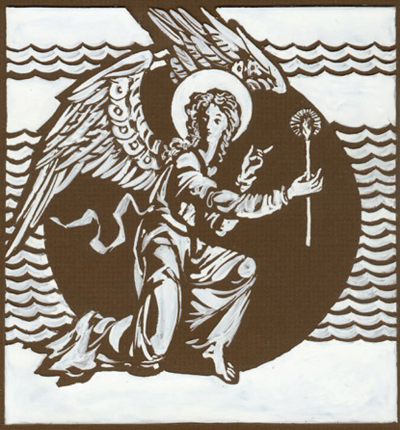

Albinas Elskus, "Cove’s Edge Angel", etching on glass, 1991

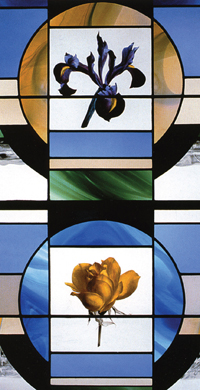

"Three Apples", 1976.

Museum of Glass, Corning, N.Y.

"Rose" (detail), 1977.

"Flowers", 1979.

"Nature’s Citric", 1978.

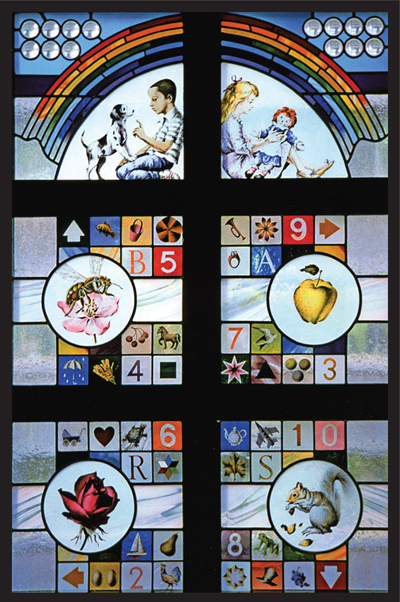

"Children’s Playroom", 1990.

Einstein-Faulk Pavilion, Mt. Sinai Medical Center, New York.

"We Shall Overcome", 1991.

Civil Rights Memorial Window,

Cornell University Sage Chapel,

Ithaca, N.Y.